There must be something about fighting evil that instills a deep, dark desire in those doing the good deed to…become landlords. Owning property in a fantasy world is such an odd concept to begin with—there’s so much unused space on those overworlds! Who’s the tunnel-visioning nomad who walked past forty acres of free land and decided, “Yeah, this is all really nice, but I sure wish there was someone I could pay to live on it?”

The city-building/town-building trend in RPGs has died out in recent years, but veterans remember a golden age of scouting NPCs, funding building costs out of their own pockets, and rummaging in the mud for small bugs which were somehow integral to the construction process. Maybe their mucus membrane provided a strong adhesive, or perhaps they made a tasty mid-shift snack. Honestly, in a slew of games focused on moving forward through jaw-dropping reveals, end-of-the-world escalations, and bite-sized vignettes, the concept of building a permanent residence for you or anyone else was (as my roommates say about my eating habits) “pretty weird, dude.”

Perhaps there is some delicious morsel to salivate over when constructing a town from scratch. Perhaps it’s some food for thought players can snack on when they pause their nomadic journeys to return to a familiar place—maybe one they could call home? Time for reflection, time for digestion, and time for…time. It’s a remarkable challenge to convey the passage of time in RPGs considering budget constraints and strict deadlines. Character models and environments are usually static, and the idea of creating several versions of each is a pipe dream for most projects. Players can be told time has passed, but there’s little to prove it.

Enter the Town-Building Sidequest: frontload the costs of building infrastructure, find the wayward souls looking for a change in scenery, and stop in occasionally to see how they’re doing. Custom towns serve as stop-gaps in RPGs and are often a task segmented into parts. Over time, the land you are lording cooks itself up into a fine dish of history. On your return, a new development awaits, a child has been born, an old man has died, or a bandit is repenting for his crimes. The ebb and flow of the city you build intermittently between main story progress adorns it with a succulent garnish of the passage of time. It can reframe what may feel like a few moments or days into weeks and months. This is true in RPGs, at least.

There’s plenty of city building, world building, galaxy building, and so on out there. Some games are centered around this concept. But a city-building game doesn’t serve the same purpose as the town-building side quests of RPGs. City-building games want to pass real-world time. Town-building in RPGs passes narrative time. As such, early examples of this specific town-building are a little harder to come by. The earliest modern examples of a town-building side quest in an RPG are pretty snuggly in the SNES era when RPGs really started to cook up all kinds of different cuisine.

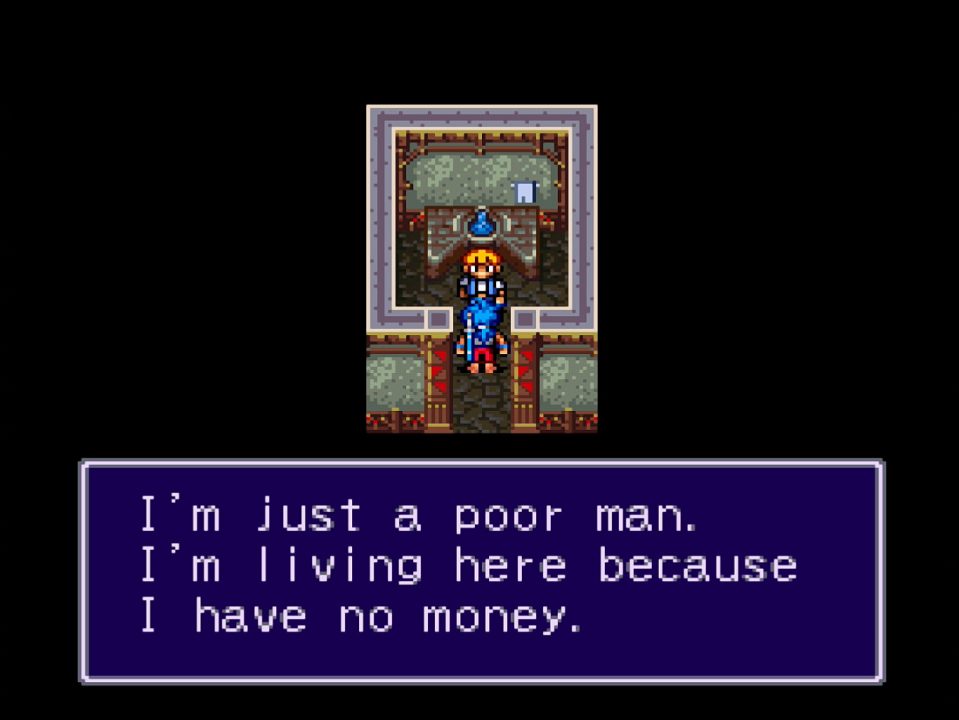

Breath of Fire 2 allows you to build your own town from scratch, inviting a handful of NPCs into what eventually grows into a functioning town. Said function depends entirely on who you ask to live there, and there’s a hard limit on how many citizens your township can have. In the best-case scenario, your town will have an armory, a rare item shop, a hint dispensary, and other beneficial resources. At worst? You can have your money stolen and be given one-time, temporary buffs from those you ask to live there. With such polarizing flavor profiles, town building has a fascinating tasting note: reaping what you sow.

You aren’t just the landlord. You’re their architect. You’re their protection. You’re their savior. The fervor with which the townsfolk congregate and praise you isn’t dissimilar to a cult.

Nothing captures the passing of time like seeing the consequences of your actions long after you’ve set them in motion. In Breath of Fire 2’s case, some of the armories your citizens build will contain powerful end-game items and equipment for you to take advantage of. Other times, you may return to TownShip and count more cats prowling around than you remember. As the story of Breath of Fire 2 progresses, your town’s facilities accumulate certain points, and they will upgrade or activate special events on certain thresholds. Still, you may need to speak to townsfolk multiple times to acquire the boon their residency provides you, or you may not gain anything but their gratitude. By the end of the township’s construction, you approach the game’s final act. You may have a bustling city of businesses and venues or a quiet hamlet of people just happy to be there. Whether or not said happiness is enough to satiate your appetite for RPG rewards is entirely up to you. It’s part of the power fantasy this type of side quest allows us to live out in a virtual space without real-world consequences.

You aren’t just the landlord. You’re their architect. You’re their protection. You’re their savior. The fervor with which the townsfolk congregate and praise you isn’t dissimilar to a cult. They defer to your judgment in all things, from who’s allowed in town to what kind of town it should be. In Dragon Quest VII, your choices shape your town into one of several archetypes, but they also shape the people living in it. Invite enough brigands and thieves to your player-created town, and it’ll develop into a casino-dominated slum. Focus more on inviting animals and farmhands, and the town will lean towards wide-scale farming production.

Your power over the town grows alongside it. You can evict tenants and have access to a list of their names and professions. Very quickly, the authority you gain over player-created towns in RPGs can become a bit of an ego trip! It also diminishes the value of your townspeople. Giving players too much control over their town runs the risk of reducing the process itself into a resource grind for powerful end-game items. NPCs begin to resemble currency; we view them as increments in favor of our bottom line. We grow impatient with their slow progress towards said bottom line. We stop appreciating those NPCs and the sense of time conveyed by our visits. So city-building mechanics which reward players for relinquishing authoritative power in favor of what their townsfolk desire better capture the positive aspects of town-building in the first place.

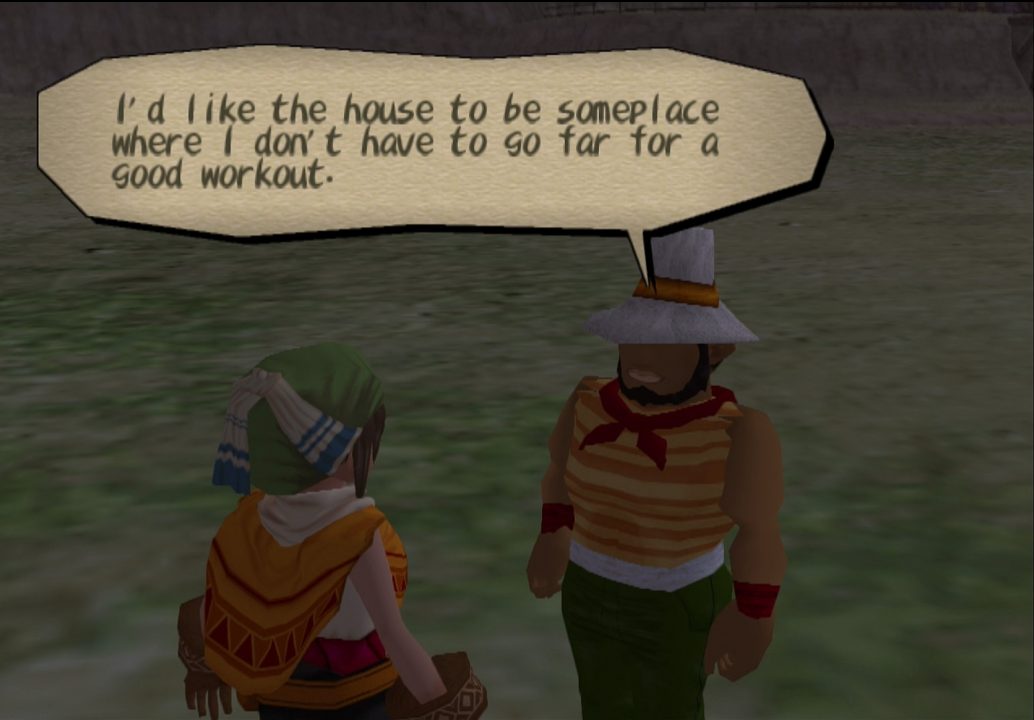

The primary value behind city building is the shared space with other characters. Building a community should be a collaborative effort, and RPGs should reward players for taking community concerns into account. RPGs should implement these sorts of ideas into their city-building mechanics to begin with. Dark Cloud is the poster child of this concept: restore the world and its people to their former lives. You recover the people and their belongings by exploring dungeons and can then rebuild various villages and towns from scratch using the assets you collect. At first, you might plop down buildings and terrain in any which way to gain access to the chests and items you can find inside them.

Soon enough, the real reward becomes obvious. The various residents of each town have requests: where they want their homes, who they wish to live next to, and what they’d prefer to have near their property. Completing all requests in a village will yield a much better reward than any of the consumable items individual buildings or people can give you, so the player is pushed to be receptive to resident concerns. Through the promise of reward or out of the kindness of their hearts, Dark Cloud’s city-building mechanics get players interacting with NPCs and learning more about them.

In this way, city building is the player’s anchor to an RPG’s world, causing them to take up permanent residence in a universe they’d only be a visitor to otherwise. It’s easy to grow fond of specific characters and, at least in Dark Cloud’s case, potentially grow more and more annoyed by the pickier ones with ultra-specific requests. But forming opinions about the less-important elements of the world and having an emotional response to a tertiary character you wouldn’t expect is part of maintaining your stay. There’s a chance to find respite when you return to your township or kingdom and tweak a few things here and there—the equivalent of adjusting a painting on the wall or adding a new trinket on the shelf. Relaxing into the tranquility of a space untouched by the conflict of the narrative to decide, “yeah, this is a good place to stop and take a break.” It’s your home away from home. A hero’s home! And without them, our journey through the RPGs we play would be a little less savory.