“Souls-like” is a somewhat exhausting term. It gets thrown around a lot in a gaming landscape where titles are endlessly compared to Demon’s Souls and FromSoftware’s oeuvre since then. Regardless of whether you think Souls-like is a “real” genre, it’s helped lump the many games that flagrantly lift the aesthetics and design of FromSoftware’s history-shifting work (e.g. sci-fi Dark Souls, 2D Dark Souls, anime Dark Souls, Pinocchio Bloodborne) for fans with an unquenchable thirst for that winning formula of demanding mechanical precision and sparse, atmospheric storytelling.

I’ve played most of the Souls-likes listed above and appreciated the hard work that went into trying to bottle and riff off that FromSoftware magic. Still, I couldn’t get it out of my head that I was experiencing a mere imitation of something more real. I never thought a game starring a protagonist who looks like he could be the nephew of Sebastian from The Little Mermaid would be the first Souls-like that bravely crawls far enough out of FromSoft’s shell that it makes the label feel like a launching pad for creativity rather than a game design bible.

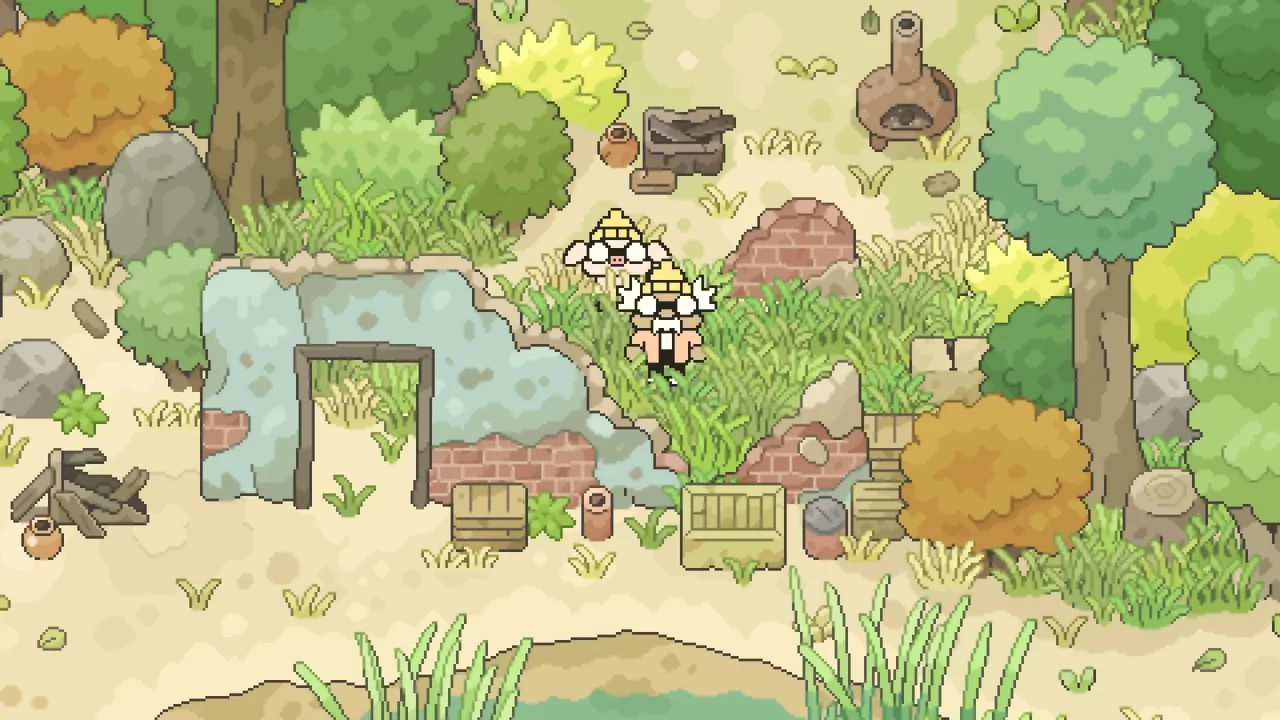

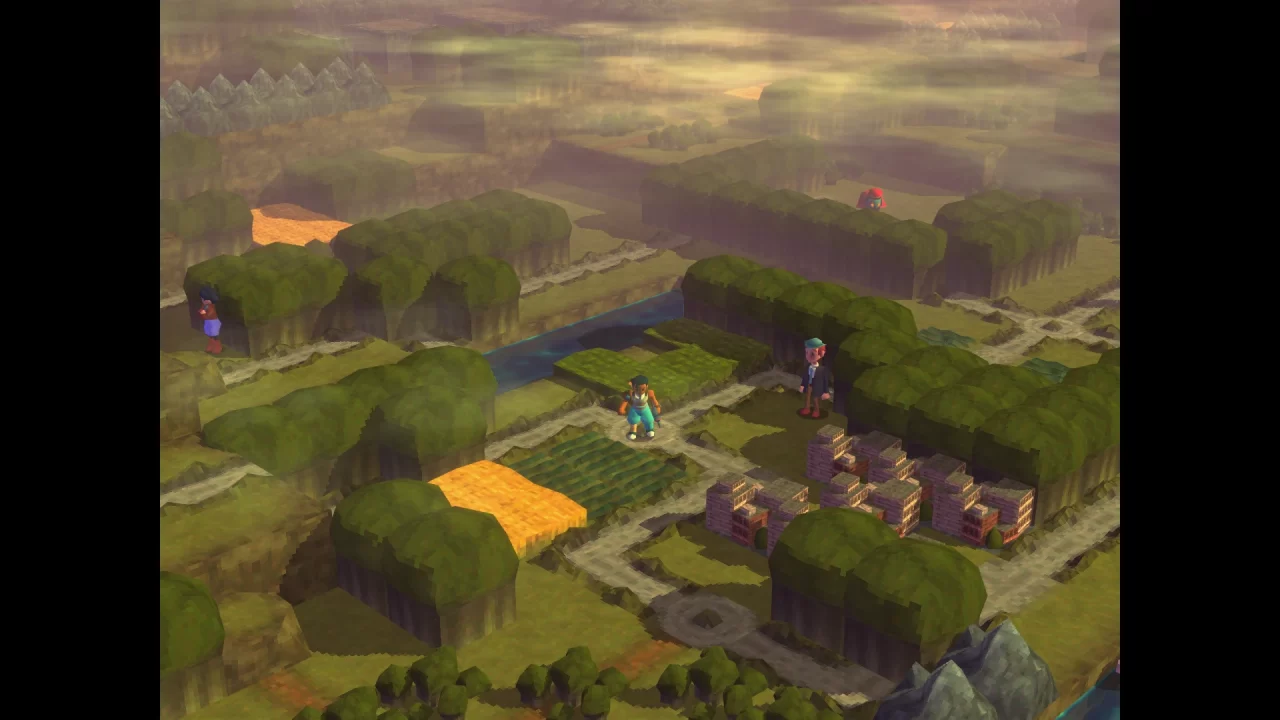

Indie studio Aggro Crab self-published Another Crab’s Treasure in 2024 following a lengthy development cycle. On one hand, it fits comfortably into the Souls-like label. As Kril the hermit crab, you explore semi-open levels, scouring for cleverly placed items and engaging in punishing combat with any fish or crustacean whose personal space you violate. On the other hand, the level design requires navigation and 3D platforming that sometimes feels as reminiscent of late-90s Rare as 2010s FromSoft. Holding the jump button to extend Kril’s waterborne movement by swimming is reminiscent of Kazooie flapping her wings to keep Banjo afloat. It’s an ambitious expansion of genre influences that feels impressively natural.

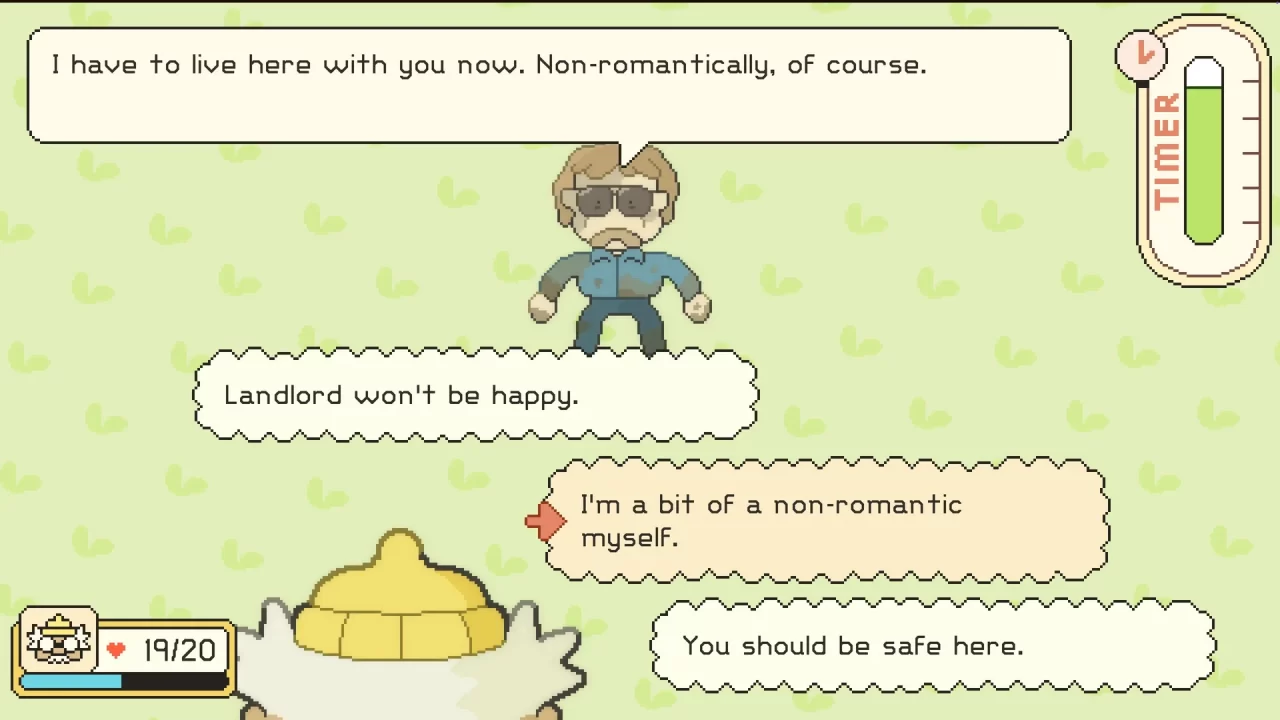

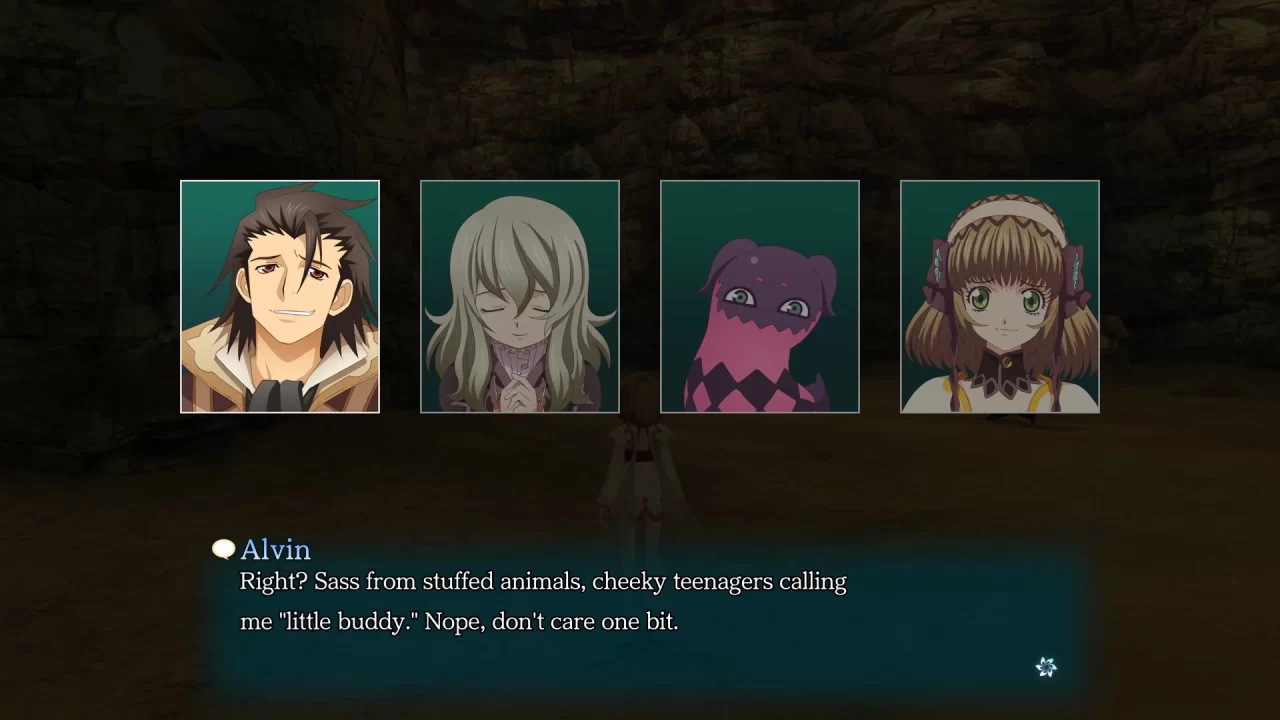

As someone who enjoys FromSoft’s moody aesthetics, I have to admit I was initially put off by Another Crab’s Treasure’s cartoonish visuals and punny writing. The storytelling is more straightforward here with established characters and dialogue that has some interest in explaining things to you. As I played past the initial hour, though, this superficial judgment faded away as the darker thematic richness that lurks in these ocean depths began to surface. Driving Kril’s journey is a surprisingly thoughtful story about the perils of environmental harm and capitalistic exploitation. And really, what’s more tragic: the hubris and downfall of Lord Gwyn and his empire, or the destruction human waste has wrought on our Earth’s beautiful, expansive oceans?

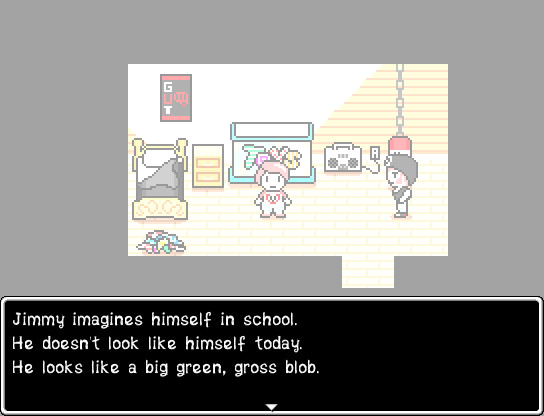

To start things off, a literal loan shark seizes ownership of Kril’s shell and disrupts his peacefully solitary life on the ocean coast. After giving chase, he ends up on the seabed where things… don’t look so good. The first fellow crab he meets has a hollow look in its eyes and attacks Kril. Turns out this widespread hostility is due to the Gunk spreading throughout the sea, which appears to result from the excessive waste plaguing the ocean floor. Desperate times have also driven the remaining sane creatures towards power grabs and exploitation.

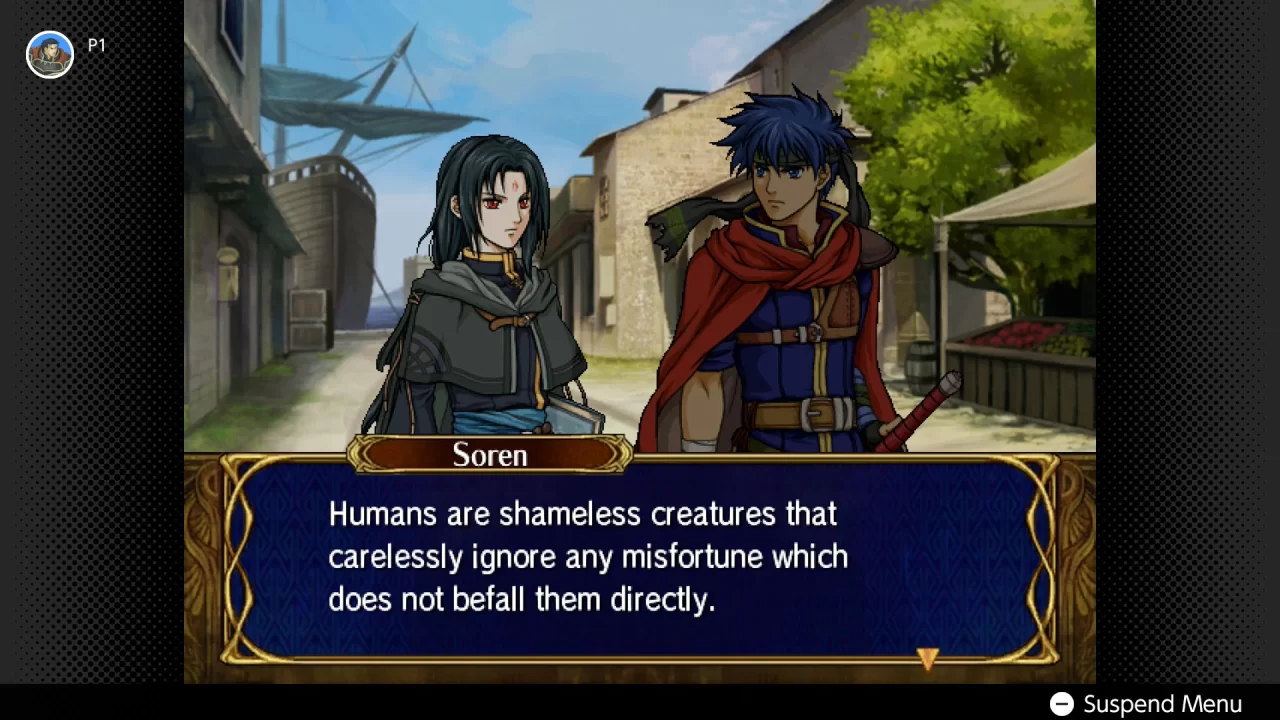

This should all be a reality check for Kril, who displays a privileged “out of sight, out of mind” social philosophy. All he wants is to get his shell back and return to his hermetic life away from this hopeless, depressing reality. He’s a relatable character, to say the least.

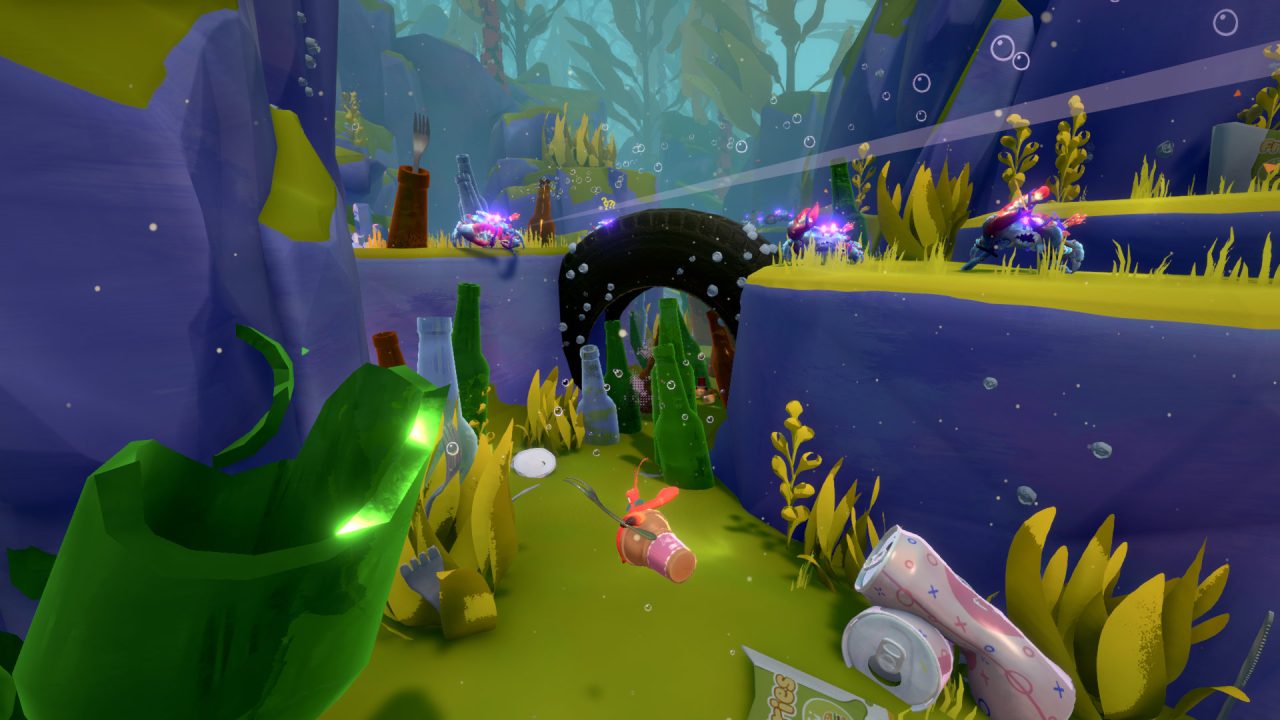

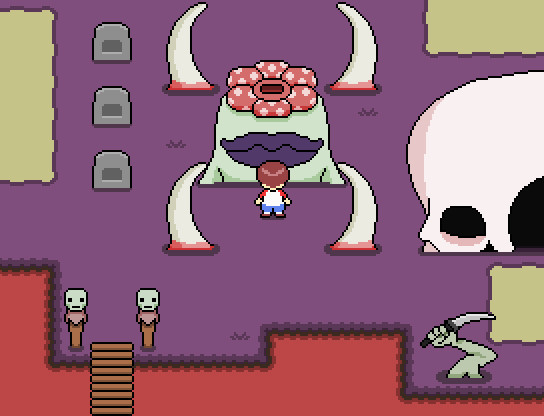

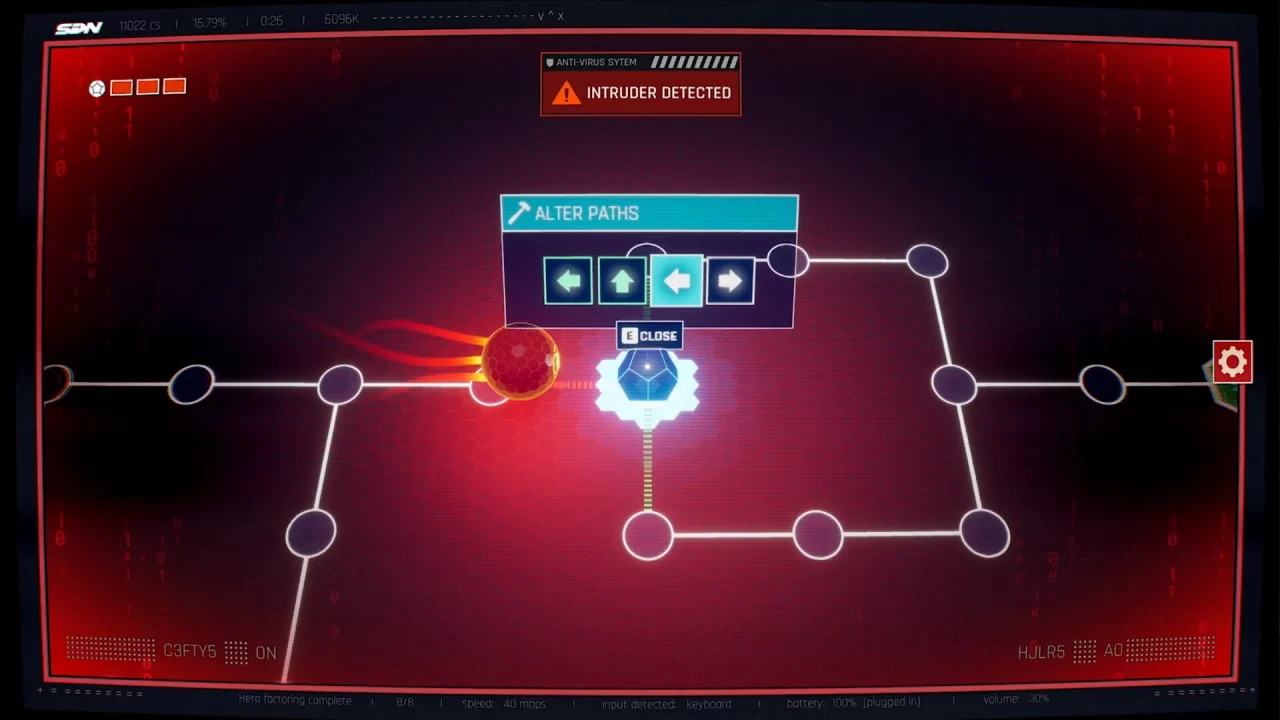

The world in Another Crab’s Treasure is built around the ways a society of crustaceans has adapted to all the trash and Gunk that now surrounds them. This fantastical yet alarmingly real premise manifests smoothly into the game’s own take on environmental storytelling and its iterations on Souls-like mechanics.

The creative level design delights with environments based on oceanic biomes made unnatural by all the litter that’s conveniently laid out as a platforming playground. As Kril is navigating these areas, you’ll be reminded of all the things you’ve thrown in the trash—from plastic toys to pizza boxes to electronics. Each main area is a distinct space with plenty of challenges and hidden items to discover. They all scratch that Souls itch while feeling fresh to navigate.

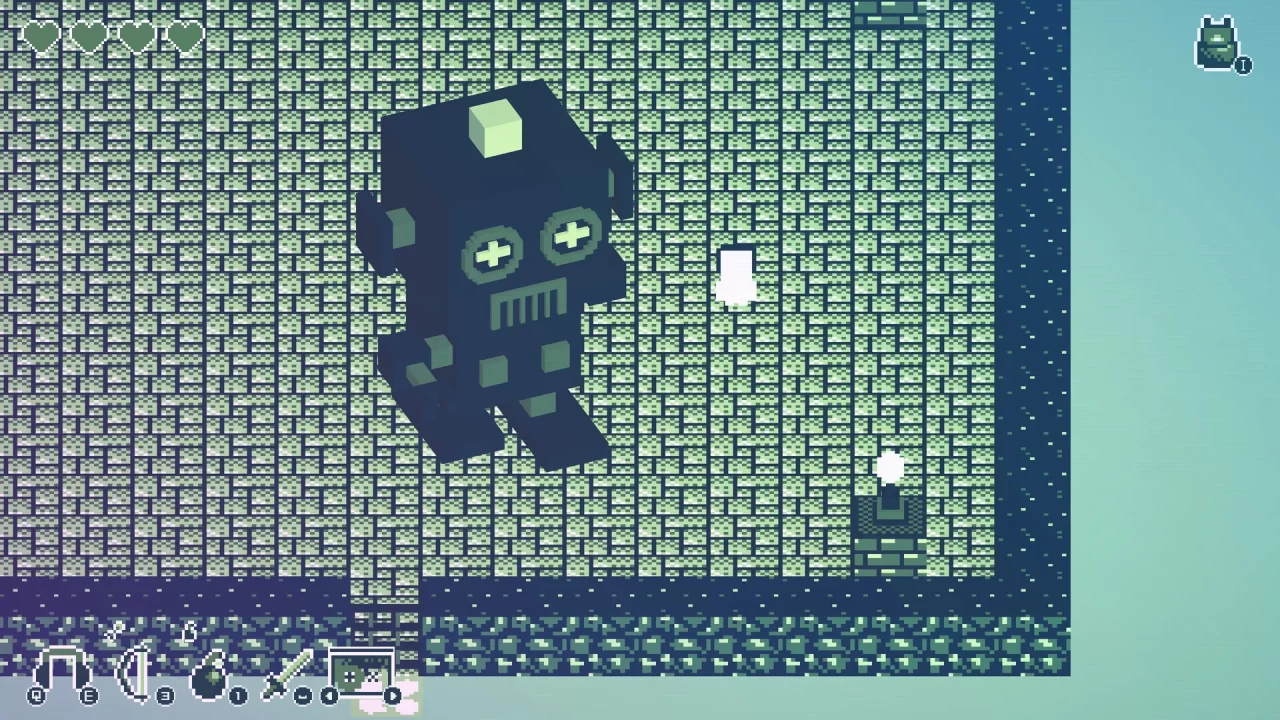

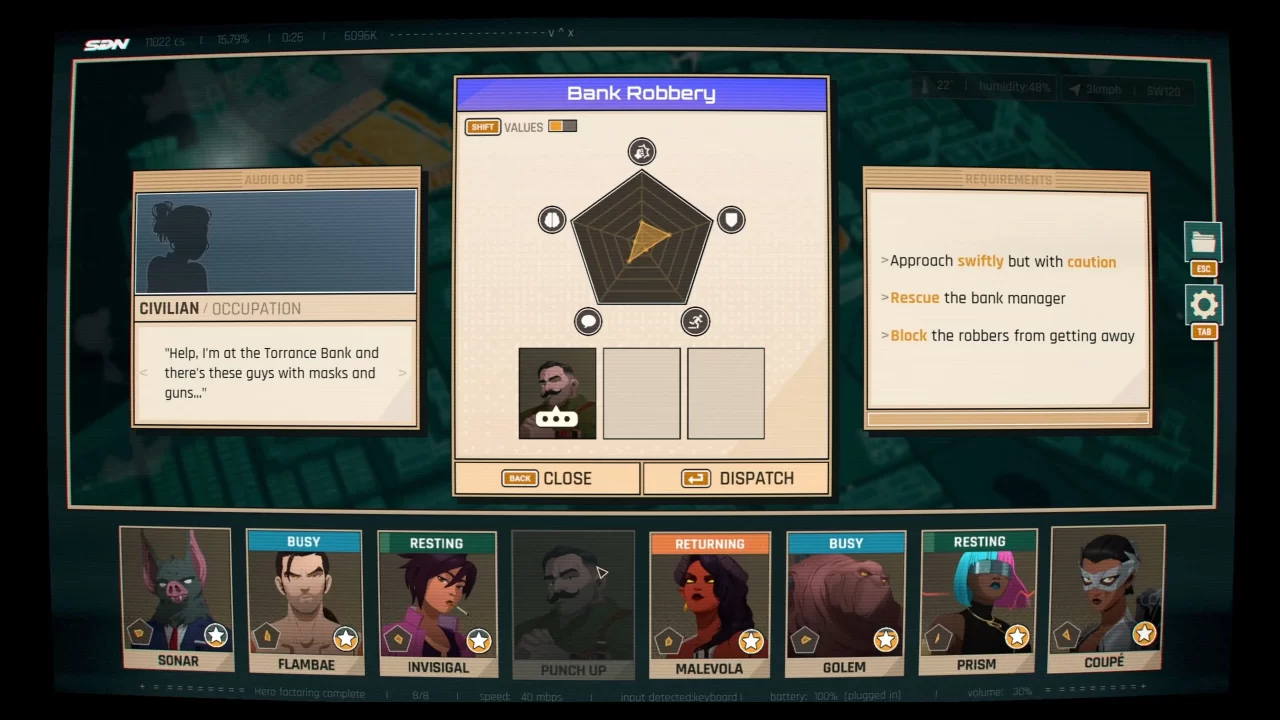

Smaller trash also has its purpose. As I said, Kril had his shell stolen, which makes our little misanthrope quite vulnerable. Fortunately, the ocean floors are littered with dozens of potential substitute “shells” that can be equipped as both Kril’s armor and shield. I’m talking tin cans, bottle caps, ink cartridges, tennis balls, and much more. It’s quite cute and disturbing at the same time, which sums up a lot of what Another Crab’s Treasure is doing aesthetically and thematically. Each shell comes with health determining its durability, weight that affects the speed of your dodge roll while wearing it, and one of 23 potential abilities. Oh, and style points, of course.

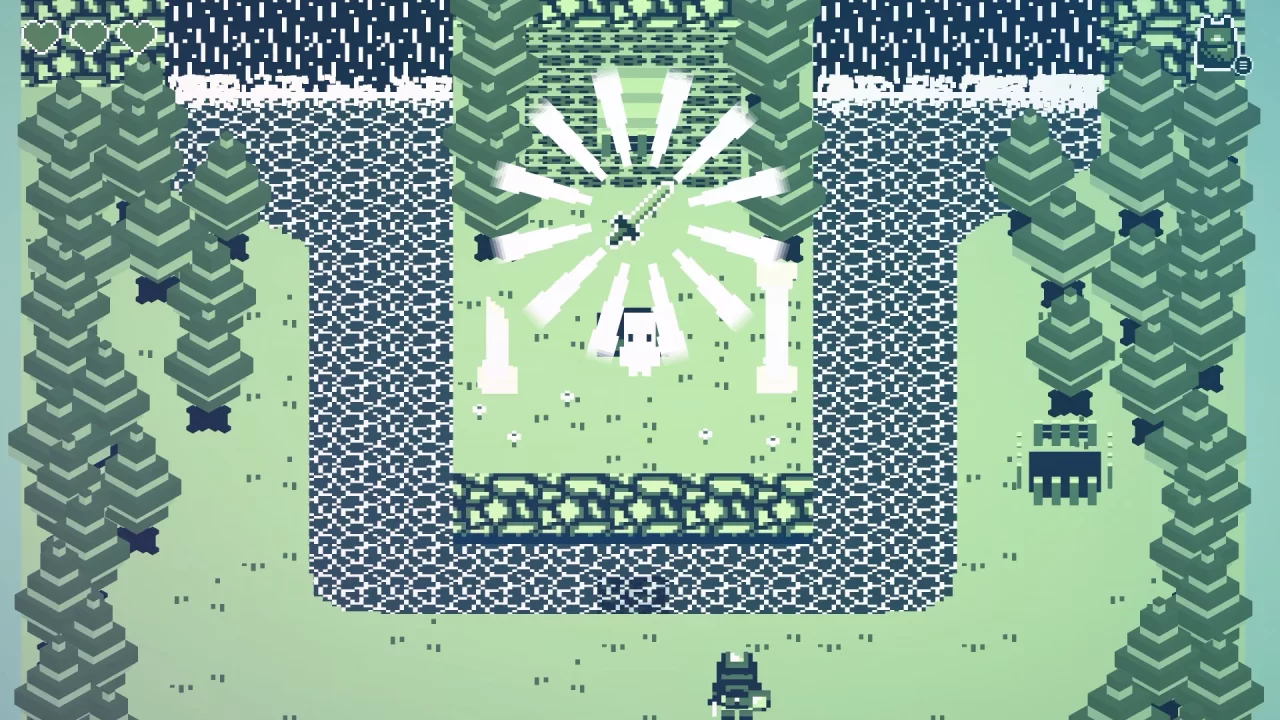

Shell durability is an important way for the combat to focalize blocking and encourage experimentation while punishing pure turtling. I found the combat flows best when going toe-to-toe with enemies, blocking carefully while aggressively counterattacking whenever an opportunity presents itself. The game has a unique approach to parries where you must release block at the time of an enemy’s attack. It’s a tricky window to nail down after so many games have conditioned me to tap for a parry, but the difference is a smart fit for the rest of the design.

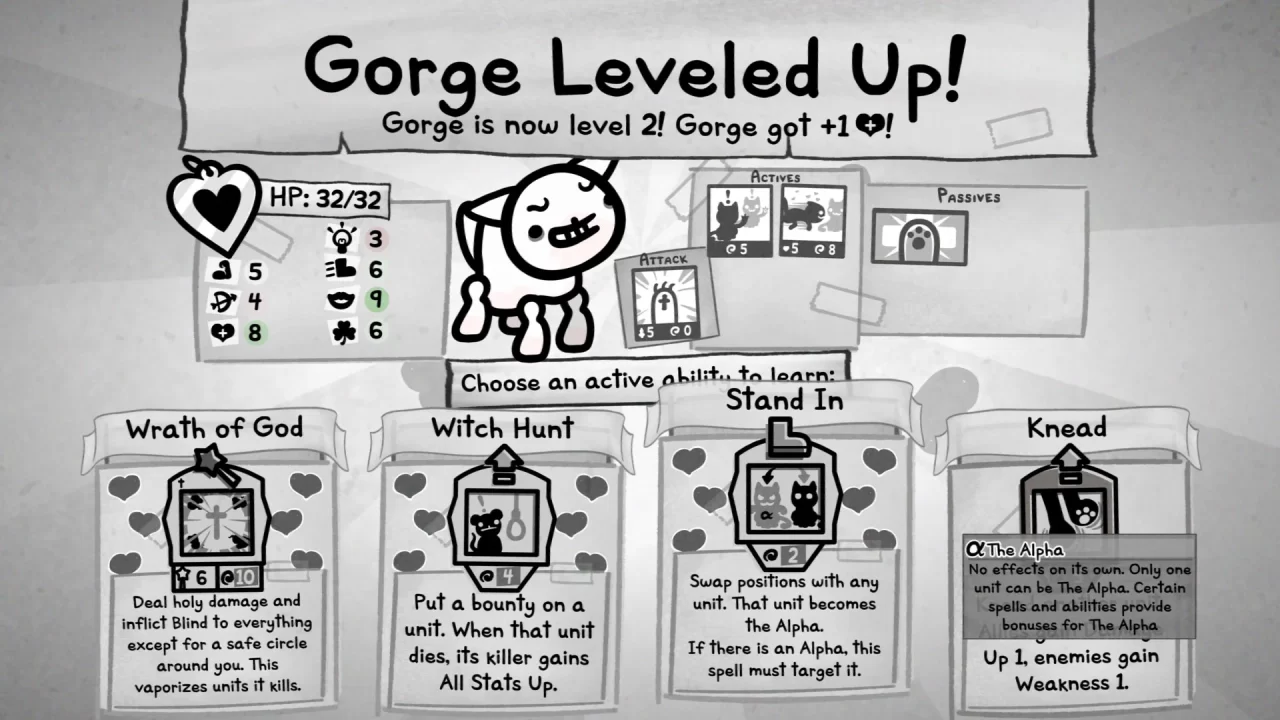

On the offensive end, Kril’s weapon of choice is a fork. It can be upgraded but it’s the only primary weapon you get. If that sounds boring, allow me to introduce you to the wonderful world of Umami. Seriously, Umami is the game’s term for magic and the skills that consume your Umami charges, and they scale with Kril’s MSG stat (you gotta love it). Shell abilities consume Umami, as do Adaptations. Adaptations are flashy moves you’ll learn that range from a sweeping, debilitating claw swing, a sea urchin sticky mine, and a bubble-blasting gun. You can also find and purchase Stowaways—equippable accessories that modify Kril’s stats or have other properties.

What I’ll give most Souls-likes over Another Crab’s Treasure is a level of mechanical polish achieved from faithful iteration on what FromSoft laid down. The first few hours of fighting in the game felt a bit undercooked for this reason, but the joy of combat picks up when you start earning Adaptations and progressing Kril’s skill trees.

By the back half of this 20-plus hour journey, your toolkit allows for enough mechanical expression that the game’s lack of build and weapon variety feels like less of an issue. With that said, not all of it is carefully balanced, so much of the game’s challenge can be mitigated at that point. There were a few climactic boss fights that went down rather unceremoniously.

Still, this is coming from someone who’s played most modern FromSoft games more than once. The uninitiated might be relieved to hear that not only is Another Crab’s Treasure a less demanding Souls-like, but it even comes with a generous menu of accessibility options to make easing into the playstyle more… well, accessible. Players can pick and choose from these options, such as Extra Shell Durability, Lower Enemy Health, and Prevent Microplastic [read: souls] Loss on Death. Honestly, it’s a brilliant way for the designers to maintain the Souls-like convention of One Difficulty to Rule Them All while offering some flexibility for inexperienced players to find their bearings without getting discouraged.

Alongside the intended standard difficulty, Another Crab’s Treasure has technical hitches that led to some extra unintended difficulty. During my playthrough, I experienced issues with fall respawn points, enemy tethering, character/environmental collisions, and other awkward frustrations to which “git gud” logic does not apply. I understand this is a consequence of the ambitious design I’ve been praising from this relatively small team, but it did temporarily spoil the good fun I was having a few too many times. On top of that, there were occasional performance drops that were surprising to see on a modern console considering this is certainly not the most technically advanced game.

Regardless, Another Crab’s Treasure is the first Souls-like I’ve played that didn’t make me feel like I may as well just replay one of the real ones. Not because it’s a better game than any of FromSoft’s modern classics, but because it’s distinct enough not to feel derivative. It’s not the most mechanically satisfying Souls-like I’ve played, but neither is the original Dark Souls, and that remains my favorite due to its ambitious creativity and clarity of vision—something Another Crab’s Treasure shares with it. Personally, I would rather developers invested in this young genre take iterative risks than churn out more FromSoft B-sides.

It helps that Another Crab’s Treasure is also a Souls-like with a soul. The game will stick with me not only because of the finest moments from its levels or boss fights, but in how cleverly and effectively its environmental concerns are baked into the whole of the experience. By the end, I was looking into ways of reducing my waste output and microplastic exposure while reflecting on what individual human “goodness” looks like in a world ravaged by our collective impact. Not bad for a game about a crab.